New Mexico Approves Master of Science in Anesthesia Program at UNM

Breathing Easier

UNM Team Studies Whether Oxygen Therapy Risks Spreading Coronavirus

When the COVID-19 pandemic came to New Mexico it brought with it many more questions than answers for frontline health care workers.

A particular worry for emergency room personnel was whether patients receiving supplemental oxygen for labored breathing might exhale tiny virus-laden aerosol droplets, putting their caregivers at risk of infection.

“At the beginning of COVID there were just tremendous clinical questions floating around,” says Darren Braude, MD, a professor in The University of New Mexico Department of Emergency Medicine and medical director of Lifeguard, the University’s air medical transport program.

COVID patients fare better if they can avoid being intubated and placed on a mechanical ventilator, Braude says. “There are certain strategies that we like to use to avoid intubation that involve high flows of oxygen,” he says. “If they’re breathing in a lot more oxygen, it has to go out somewhere – therefore, there’s a concern about generating aerosols.”

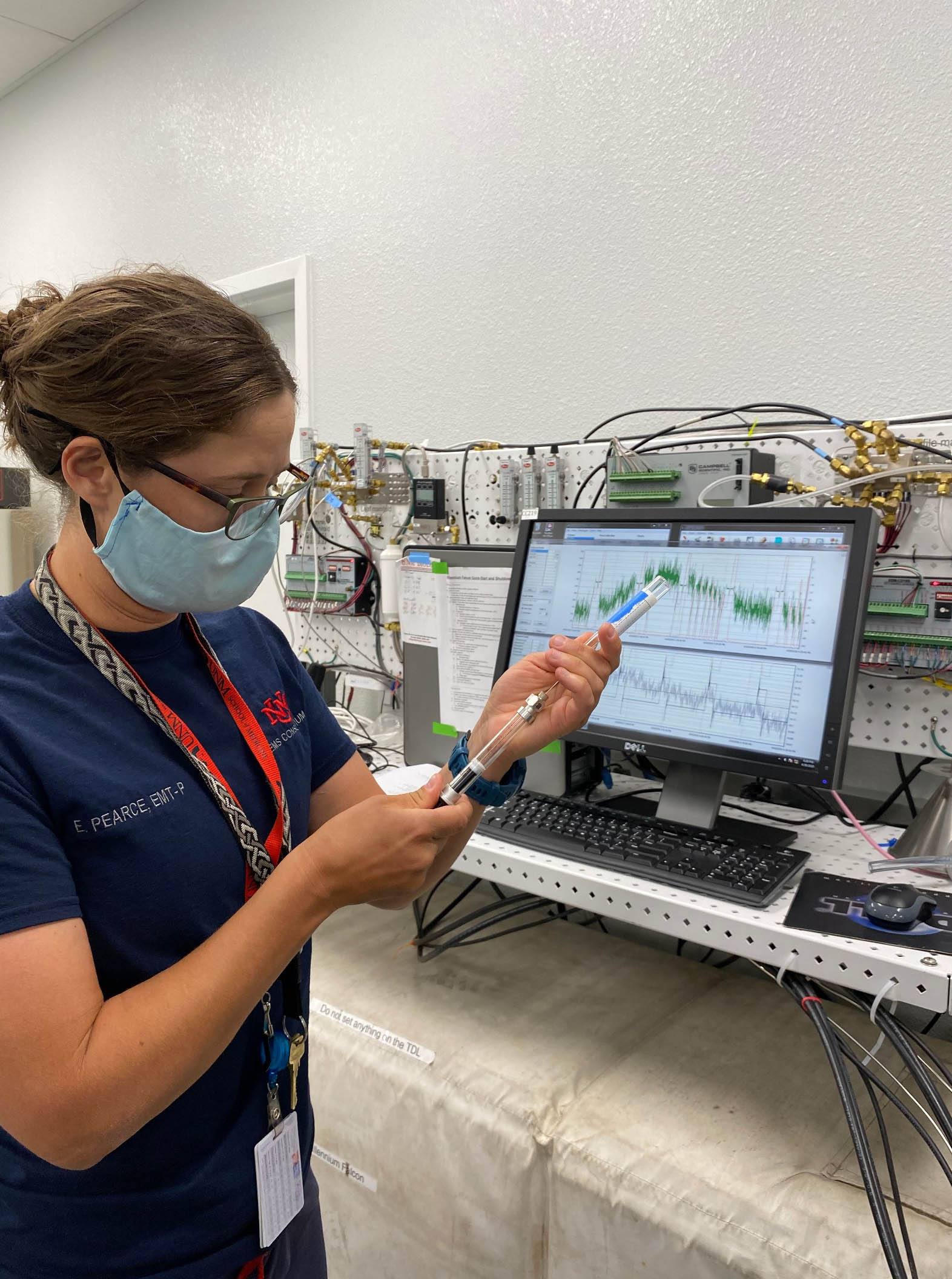

To better understand the problem, Braude pulled together a research team that included colleagues from Emergency Medicine, the UNM Department of Biology, the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep, and the College of Pharmacy. He credits fourth-year medical student Emily Pearce, a former paramedic, with managing the study logistics.

The team members volunteered themselves as subjects for their study, published this week in the Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open.

Each volunteer would don an oxygenation device, such as a nasal canula, which delivers a continuous flow of oxygen, or a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) mask, similar to those used to treat sleep apnea, while having their respiration monitored.

“One of the eye-opening things was just wearing these devices and experiencing what a patient experiences,” says Matt Campen, PhD, a College of Pharmacy professor who specializes in studying the health effects of inhaled particulates.

To assess the different oxygenation techniques, Campen used a laser aerosol spectrometer that detected tiny particles as they were exhaled. The study subjects were tested while wearing the oxygenation devices alone and while wearing procedure masks over them.

“The nasal canula, at a very high flow, leads to a lot of particulates coming out,” Campen says, “Whereas the CPAP device has very self-contained plumbing. It seemed to be much more protective.”

A year into the pandemic, much more is known about how the virus is transmitted, and how best to protect from becoming infected, Braude says.

“In hindsight some of the answers are not as critical as they were when we started,” he says. “We really thought if a patient was generating a lot of aerosols somebody was bound to get sick and somebody was going to die. We have come to find out if we are wearing the right PPE we can safely care for somebody who is generating aerosols.”

The study results are still relevant for situations in which a COVID-positive patient is being transported in a helicopter or small airplane. “We’re in these very confined spaces that aren’t as ventilated,” Braude says.

“We did discover that at very high flows – especially with the nasal canula – we’re generating tremendous amounts of aerosols, even with a mask. That’s probably worth thinking about, for the safety of the flight crew.”

Oxygen support is critical for patients who are being transported across long distances in a helicopter or an airplane, Braude says. “Now we have that much more information to try to inform those decisions.”